The Second-Order Effects of Apple's Privacy Push

How the fallout from SKAdnetwork and Cookie Deprecation could be worse than the benefits

Disclosure: I am the CEO of a growth marketing agency that helps consumer technology companies (mostly startups) manage advertising on Facebook and Google. My concerns have a bias toward an open and fair competitive landscape online.

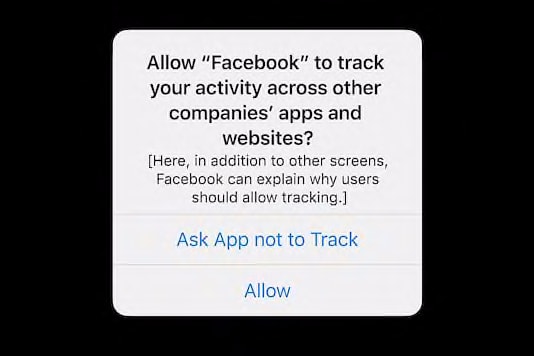

Apple is altering their operating system and web browsers to require their users to explicitly “opt in” to vendors tracking their device across apps and websites. This functionality has been “opt out” until now, which means users were opted in by default.

At first blush, this shift toward explicit user permission seems good for users and fairly innocuous to the well-intentioned developers of our favorite apps and websites.

Why would they need to track your personal devices across other apps and websites anyways? Well, the answer is a lot more nuanced than you’d think.

Apple’s App Store economy is very robust. It facilitates more than half a trillion dollars in commerce per year. The App Store is comparable to the GDP of Sweden or Thailand, but with orders of magnitude more market participation. This policy change will impact the lives and livelihoods of a billion+ participants both big and small.

I worry that this likely well-intentioned change may do more harm than good, primarily because of second-order effects.

How this will make the digital advertising rich even richer

I worry that this adjustment in privacy policy is likely to make the richest participants of the App Store ecosystem even richer.

Why? Well, this is where the nuance I mention above starts to come in.

The primary reason that 99% of app and website developers track you across other apps and websites is simple and relatively harmless. It’s just to tell them how you found out about their app or website.

When a developer creates a digital product, there is virtually no way for them to convince people to try it other than (1) being featured in the App Store (which Apple decides) or (2) advertising on other apps and websites, the largest of which are run but Facebook, Google, Amazon, and Apple itself.

Because of this current market dynamic, when users opt out of this tracking, it will overwhelmingly harm small tech companies who are using this functionality simply to attribute where they are getting users from.

Large participants, namely Facebook, Google, and Apple itself, already have all of the data they could ever need about you and your device from the data you share when using their own apps. They don’t need to track you across third party apps to know where you came from. You’re most likely already on their products and have been for some time.

If the large market participants keep all of the data they already have and small upstarts can never accrue any cross-app and site data in the future to compete against them, it may exacerbate a dynamic that already exists where the only way to grow your business is to pay Facebook, Google, and Apple for access to customer relationships via ads.

This feels like a more serious decision for users.

Do we really want to be locked in to using Facebook, Google, and Apple forever being the gatekeepers of what new apps and websites we find out about because they have all of the data and no competitors can accrue it? This future is feeling more likely.

How this will further consolidate online commerce

The second-order effects of this policy change are not just App Store or advertising specific. They will impact all digital commerce broadly, at a critical time when digital commerce is exploding in just about every vertical due to pandemic tailwinds.

While Facebook, Google, and other large market players in digital advertising will keep all of the user data they have already collected, there is an important stream of data that will be break for them on a go-forward basis for opted out users.

That data is an “activity stream” that their advertisers share with them after a user clicks an ad and lands on the advertiser’s site or app.

Now that the big ad networks will be unable to have a complete view of usage data on their advertising clients’ sites, Apple is introducing a massive incentive for them to simply pull more interactions “on platform”.

Instead of smaller brands paying Facebook and Google for traffic and the ability to form long-term, direct customer relationships, we may be moving toward a future where we have to pay them for one-off customer transactions with no idea who our customers are, similar to how selling on Amazon, “Apple login”, Instagram Shops works today.

Facebook, Google, Snapchat, Pinterest, etc are already pushing to ensure that more of the shopping/commerce interactions and transactions take place on their platforms. They are incentivized to do this so they can maintain full user visibility, while the brands paying them do not. I fear that Apple’s change in privacy stance will only exacerbate this incentive.

This seems like a serious decision for users as well.

Do we really want an even bigger majority of our online transaction volume taking place on Facebook, Google, Apple, and Amazon in the future or do we want to better enable direct relationships with our favorite upstart brands? As of now, we’re already in a world where Facebook, Google, Apple, and Amazon serve as our entertainment, our news, and our shopping malls. This may only increase.

How this sets a suboptimal precedent for Online Privacy

Last but not least, the second-order effect that I worry about most.

We, as a society, are being led to a definition of Online Privacy by a private technology corporations.

However good Apple’s intent, we should be governing Apple and other technology firms with common guidelines as to what Online Privacy rights and functionalities our citizens have a right to at a societal level.

We also need to govern the rules about our post-privacy relationship with technology companies and our government. When our data has already been shared, what are the limits of personal data usage by those who hold it? What are our rights to claw it back?

Until then we address these bigger issues as a society, all participants both big and small will be subject to the action and counteraction of technology businesses, each of whom just *might* have other incentives than our individual privacy.

For now, we’ll all be presented with the binary choice below, which is everything but binary in reality. What will we choose?